Di-di, mono-di, mono-mono. I heard these terms for the first time from my OB as soon as I learned I was having twins. After my OB threw a bunch of twin jargon at me, I knew it was time to begin my homework. What were these other types of twins that I did not know about? Why were some types more risky to carry than others? What was I to expect during this twin pregnancy?

Fraternal twins

Identical twins: di-di and mo-di

Identical twins: mo-mo

Identifying twin type in early pregnancy

Fraternal twins

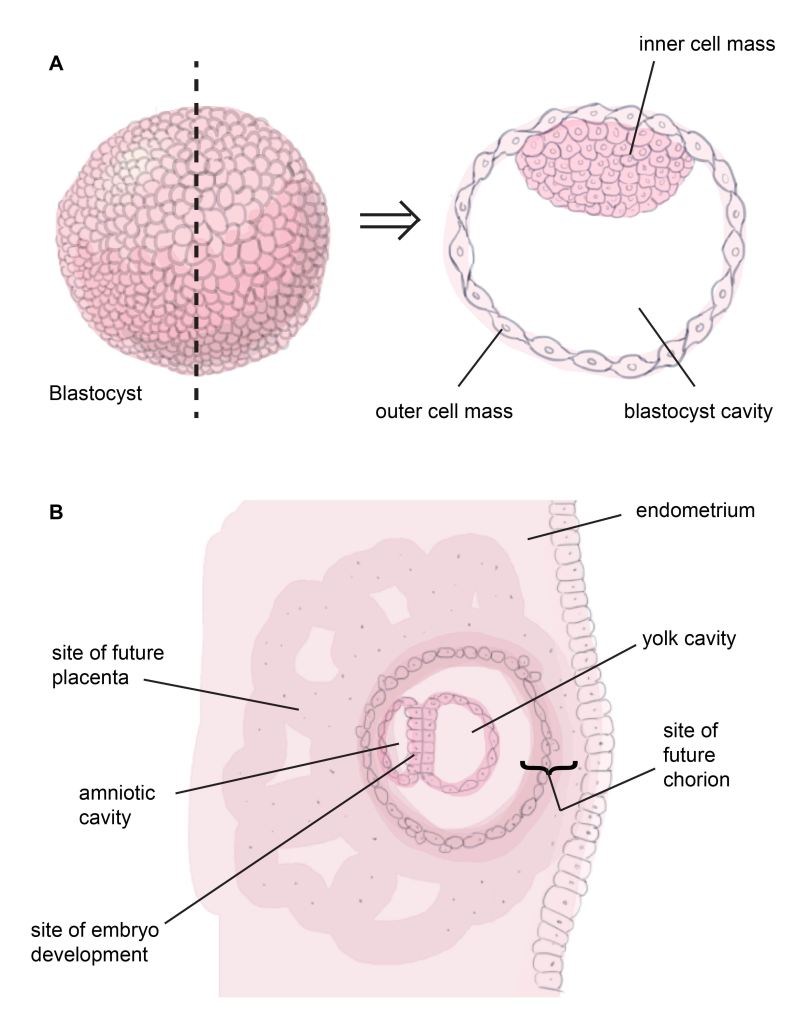

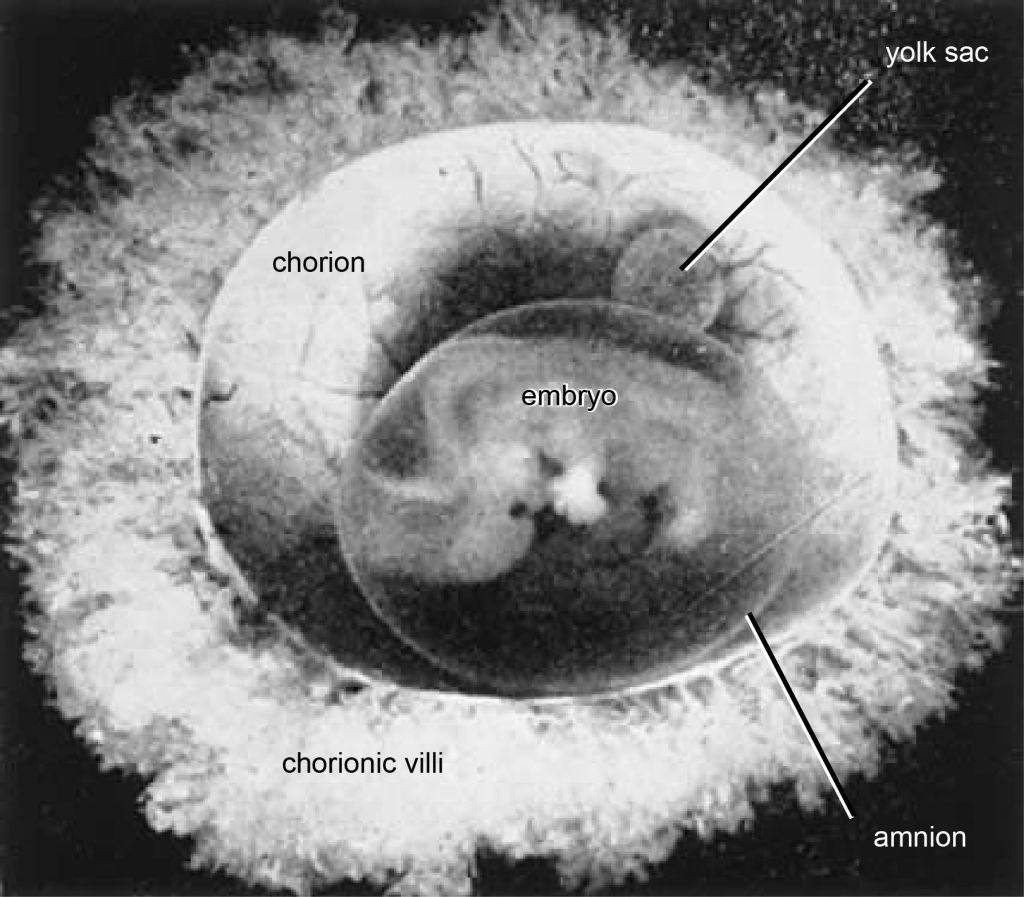

Broadly speaking, there are two types of twins: fraternal and identical. A mother can release two eggs simultaneously, and each one can be fertilized and implant itself into the endometrium of her uterus. Because these twins arise from two separately fertilized eggs, they are termed dizygotic (di-two, zygote=fertilized egg). They grow like any other embryo (Fig. 1). After about four days of cell division, each fertilized egg, or zygote, forms a hollow cavity and is called a blastocyst (Fig. 1A). The blastocyst contains an outer sphere of cells that will play a role in implantation, and an inner mass of cells that will develop into the embryo, its nutritive yolk sac, and its protective amnion. A week after fertilization, the zygote will have completely burrowed into the mother’s endometrium (Fig. 1B). In the endometrium, cells from the outer cell mass proliferate and will contribute to the chorionic membrane and placenta. The inner cell mass begins to differentiate into a dorsal mass and a ventral mass. Cavities form in the dorsal mass and the ventral mass. The ventral mass will develop into the yolk, which nourishes the embryo until the placenta is developed. The dorsal mass forms a cavity called the amniotic cavity, which will grow with the embryo and fill with fluid. The cells of the dorsal mass contacting the chorion will develop as the amniotic membrane while the cells contacting the yolk will develop as the embryo. Because two fertilized eggs have each buried themselves into the mother’s uterus, each baby develops its own chorion/placenta, and its own amnion (Fig. 2). Therefore, these twins are dichorionic-diamniotic or di-di. Dizygotic twins are as genetically similar to one another as any other sibling pair, and are known more colloquially as fraternal twins.

Identical twins: di-di and mo-di

The second type of twin, identical twins, is where twin classification becomes a little more complicated. They are termed identical because their DNA is nearly 100% identical. This happens when a mother releases one egg, as she ought to, but then after fertilization that egg throws a curve ball at her and splits itself into two zygotes! Because these two zygotes began as one, identical twins are also called monozygotic (mono-one, zygote=fertilized egg). Why would a zygote split? The cause is not yet well understood, but what is known is that for a brief moment during cell division, the tight connections between cells of the zygote lose integrity and the mass of future embryonic cells splits apart. If the split occurred very early, within the first three days after fertilization while the zygote is still aiming for the perfect real estate in the mother’s uterus, they will each develop their own chorion, placenta, and amnion (Fig. 3A). They will become, you guessed it, di-di twins. Just like fraternal twins! Only, remember, these twins have 100% of each other’s DNA in common. If this zygote splits into two after it has buried itself into the endometrium and developed its chorion, but before it has developed its amnion, then each embryo will share the chorion and placenta, but dwell in their own amniotic cavity. This schism would have to occur between 4 and 7 days after fertilization (Fig. 3B) and these twins would be referred to as mono-di or mo-di.

Identical twins: mo-mo

Identical twins are pretty rare. Mo-di identical twins are actually more common than di-di identicals, despite the fact that fraternal twins (which are always di-di) are the most common type of twin overall. But the most uncommon twins of all, the rarest of the rare, are the monochorionic-monoamniotic twins, a.k.a. monoamniotic, mono-mono, and momos. They occur in 1% of all twin pregnancies. That’s about 1 in 60,000 pregnancies! These twins are susceptible to a host of problems including developmental anomalies and cord compression, along with other problems that come with having mo-di twins such as Twin-to-Twin Transfusion syndrome or TTTS.

Momo twins result from the zygote splitting after the 8th day post-fertilization (Fig. 3C). The unfortunate circumstance of splitting so late is that one of the zygotes may not acquire the proper unspecialized cells it needs to completely grow itself. Incompletely developed fetuses or midline developmental defects are more common in monoamniotic pregnancies. One could imagine that the variety of developmental issues common in momos lies on a continuum based on the timing of separation. A very late split of the zygote will result in conjoined twins, who may share a heart or part of the GI system. Sadly, such twins seldom survive long after birth, if they make it that far.

Identifying my twin type in the early first trimester

Of course as soon as I learned I was having twins, I was aching to know which type I was carrying. And like any other pregnant woman, I wanted to know their biological sex. Statistically, I was going to have boy-girl fraternal twins. Fraternal twins are 66% more common than identical twins. Further, my demographic would suggest they are likely fraternal since fraternal twins more commonly occur in non-Hispanic whites.

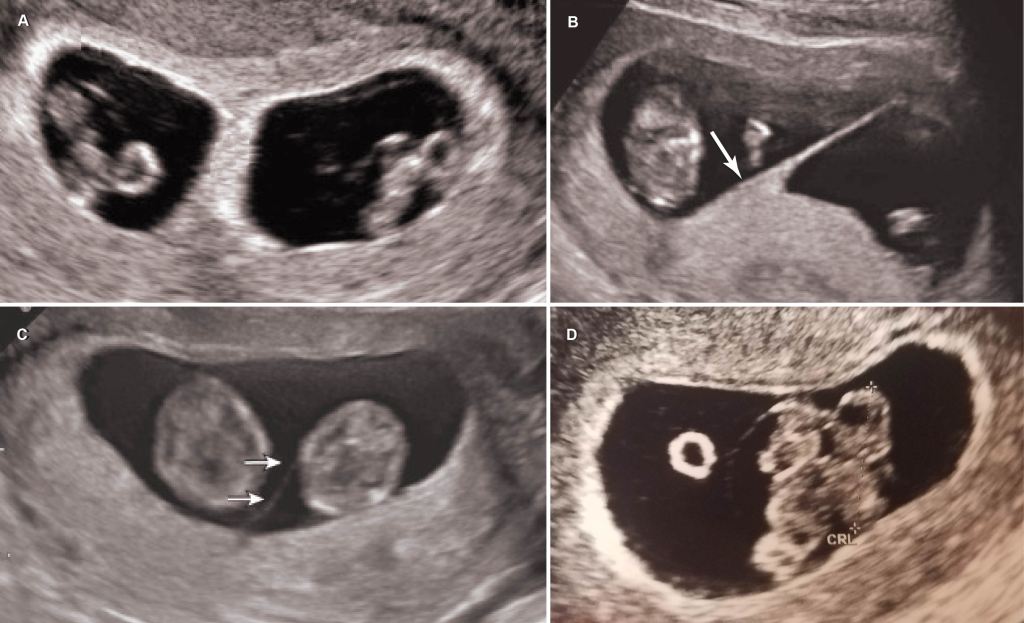

However, unlike identical twins, fraternal twins typically run in families. Fraternal twins do not run in my family. It is of no consequence to me if they run in my husband’s family since he does not affect how many eggs I release (sorry hubs, I know you like to imagine your extreme manliness can cause twins). But for the record they do not run in his family either. Therefore, my twins were a freak occurrence and quite possibly identical. Further, my ultrasounds did not look like early ultrasounds of dichorionic twins (Fig. 4A). Even though the membranes are thin at eight weeks, there is often a characteristic mountain peak or lambda shape visible where the placentae abut one another (Fig. 4B). On mine, there was no peak (Fig. 4D). Sharing a placenta would have to mean my twins were identical. So then I had a 50:50 chance of carrying boys or girls. Unless they were monoamniotic; then my chances of having two girls would double since twice the number of momos are female than male. But monoamniotic is not very likely. Could my babies be one in 60,000? No way.

Oi. I couldn’t wait for the 20-week ultrasound to answer these questions. I needed a blood test.

References

Ahokas, R.A. and McKinney, E.T. 2008. Development and physiology of the placenta and membranes. The Global Library of Women’s Medicine. ISSN: 1756-2228) 2008; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.10101

Bromley, B. and Benecerrof, B. 1995. Using the number of yolk sacs to determine amnionicity in early first trimester monochorionic twins. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 14: 415-419.

Fuchs, K.M. and D’Alton, M.E. 2018. Monochorionic monoamniotic twin gestations In J.A. Copel, M.E. D’Alton, H. Feltovich, E. Gratacós, D. Krakow, A.O. Odibo, L.D. Platt, and B. Tutschek (Eds.), Obstetric Imaging: Fetal Diagnosis and Care (pp. 642-645.e1). Elsevier, Inc. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-44548-1.00159-5

———————– 2018. Monochorionic diamniotic twin gestations In J.A. Copel, M.E. D’Alton, H. Feltovich, E. Gratacós, D. Krakow, A.O. Odibo, L.D. Platt, and B. Tutschek (Eds.), Obstetric Imaging: Fetal Diagnosis and Care (pp. 645-648.e1). Elsevier, Inc. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-44548-1.00160-1

———————– 2018. Monochorionic monoamniotic twin gestations In J.A. Copel, M.E. D’Alton, H. Feltovich, E. Gratacós, D. Krakow, A.O. Odibo, L.D. Platt, and B. Tutschek (Eds.), Obstetric Imaging: Fetal Diagnosis and Care (pp. 648-650.e1). Elsevier, Inc. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-44548-1.00161-3