Disclaimer: The following post summarizes what I learned to expect for managing my monoamniotic pregnancy. THIS POST IS NOT PROVIDING MEDICAL ADVICE. Everyone’s pregnancy is different. Consult your obstetrician for medical advice; not my blog!

Cord entanglement

In-patient vs. out-patient monitoring

Gestation beyond 34 weeks

Caesarean vs. vaginal birth

By my 16th week of pregnancy, I understood that my twins were likely monoamniotic: the rarest and riskiest twin type to carry. The two weeks between my diagnosis at the perinatologist clinic and my subsequent meeting with my obstetrician were grueling. I needed assurances that my twins were going to be okay; I craved a game plan for how we were going to keep me and my girls safe (I found out my twins were identical girls in the first trimester from a blood test). I kept my mind preoccupied with research. I searched for anecdotes, and I searched for statistics. It was hard to feel optimistic based on the information readily available to anyone online, but the scientific literature published within the last five or so years had a very different tone.

How the internet makes a bad first impression

Like any complicated medical condition, initial internet searches of monoamniotic twin pregnancy reveal depressing statistics.

From obgyn-care.net: “To have an idea about the increase of vital risk, you should know that twins growing in the same sac (monochorionic, monoamniotic) have a survival rate of only 50%!”

From monoamniotic.org: “Among the couples who…were truly diagnosed as monoamniotic, 60% have had two healthy babies.”

Not very uplifting.

Maybe reading anecdotal experiences would put my mind at ease? Fortunately, there were plenty of success stories spanning five decades to assure me that monoamniotic twins were not fated to die in-utero. But some people’s stories from just within the last decade exposed the disturbing beliefs of some physicians about monoamniotic twin pregnancies. A woman pregnant with momo twins in 2008 wrote that her physician informed her that “there wasn’t much of a chance of survival” and that she could “continue…a hellacious pregnancy and still possibly lose both babies or terminate the pregnancy.” She chose to terminate and now lives with regret. Upon diagnosis of monoamniotic twins, one man in 2011 wrote that his MFM doctor offered him and his wife two options: “terminate the pregnancy, or continue.” “In many cases, we would recommend for the couple to terminate this kind of pregnancy…” the man quotes his physician.

Why were those physicians so dire? Of course without more information it is difficult to understand the complete circumstances of those pregnancies. There are many ways a monoamniotic pregnancy can be complicated with a tenuous outcome. Sudden death from cord constriction is particularly concerning and commonly cited when discussing the perils of a monoamniotic twin pregnancy. But does it justify threatening an expecting family with loss?

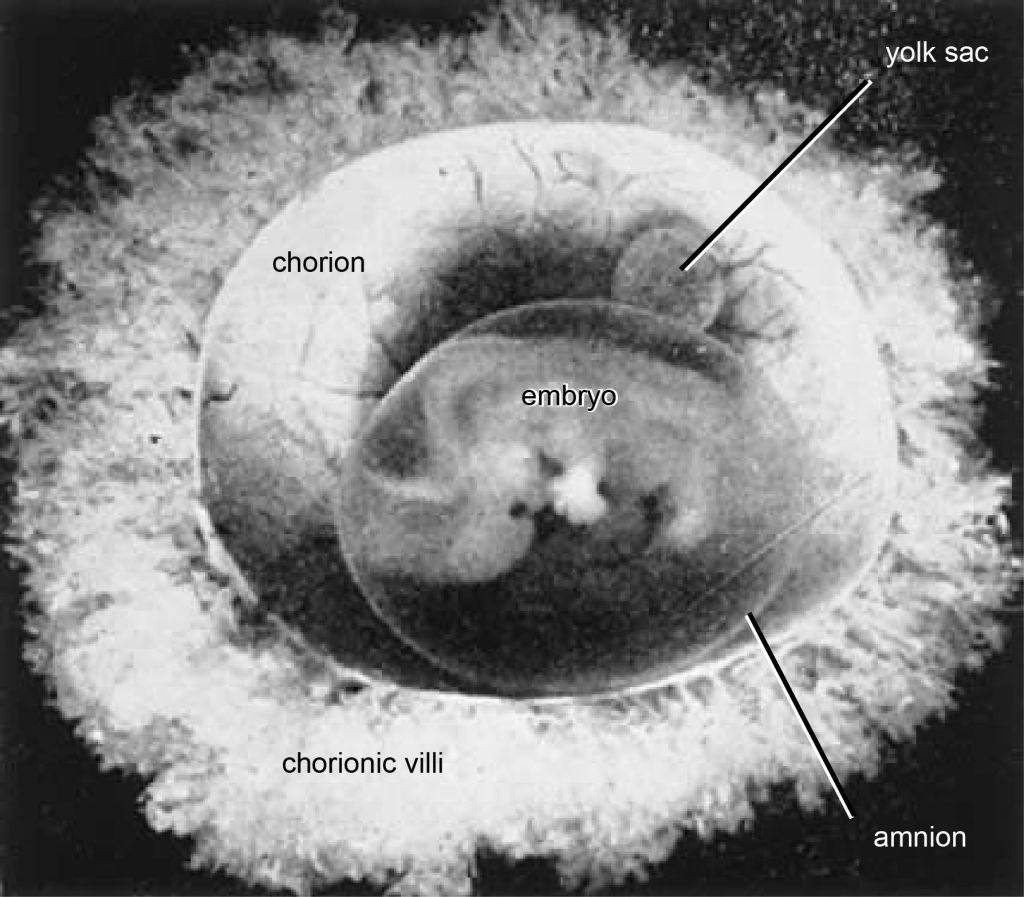

Cord entanglement in monoamniotic twins

The short answer is no, most monoamniotic twins are not going to spontaneously die from cord entanglement. The truth is, entanglement of the umbilical cord is expected in 100% of momo gestations (Dias et al., 2010)(Fig. 2). Constriction of the cords, not just entanglement, is the real threat to momos, but not all cords become so tightly knotted. Most prenatal mortality before 20 weeks results from twin-reversed arterial perfusion (TRAP), discordant anomalies, spontaneous miscarriage from developmental anomalies, conjoined twinning, and complications from prematurity, but not from cord entanglement itself (Dias et al., 2010; Rossi and Perfumo, 2013). Size discordance in monochorionic twins is a symptom of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS). If left untreated, it can lead to intrauterine death of both twins. The silver lining from expecting momo twins is that TTTS is five times less common in momos than in di-mos. This is likely due to the arterial connections present in the placenta of momos, but not typically in di-mos (Umer et al, 2003; Hack et al., 2009). However, congenital defects are more common in momos (Myrianthopoulos, 1975). So long as these congenital defects are not detected in the 20 week anatomy scan and the succeeding echocardiogram around 24 weeks, a family expecting momos can breathe a sigh of relief, for the outcome of developmentally normal monoamniotic twins after 20 weeks is likely to be positive. If the cords are twisted or even knotted to some degree, do not panic; it is not an automatic death sentence. However, do consider that as the fetuses grow in size, so too does the diameter of their cords. Therefore, the threat of any tangled and knotted cords becoming compressed occurs later in gestation. That is part of the reasoning behind delivering momo twins no later than 32-34 weeks. Fortunately, the number of spontaneous losses of momo twins has decreased since the improvement of monitoring practices toward a more intensive monitoring schedule (Roqué et al., 2009; Rossi and Perfumo, 2013).

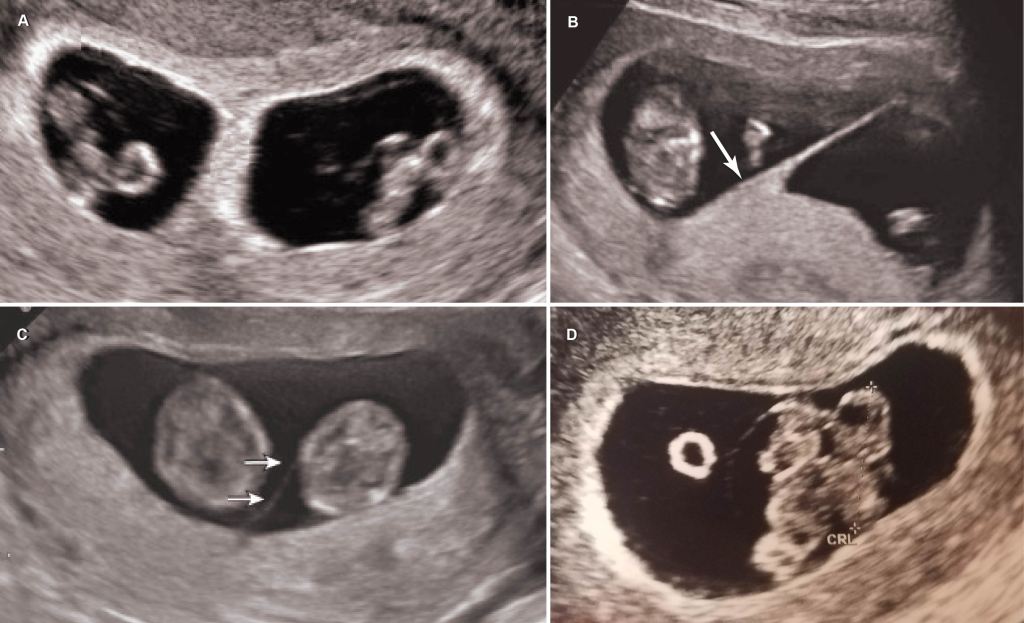

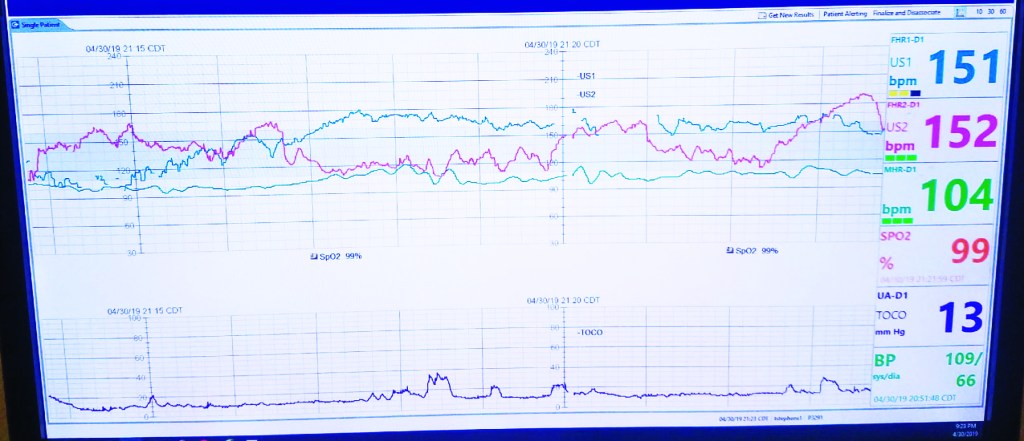

In-patient vs. out-patient monitoring

What does intensive monitoring mean when you are expecting momos? At the very least, a mother of momos can expect non-stress testing (NST) every two to three days, coming and going to her monitoring appointments at her leisure. Depending on her hospital and obstetrician policies, she can otherwise expect NSTs two to three times a day with ultrasounds twice a week (Fig. 3). Such regular monitoring would require the mother to go inpatient. That means living in the hospital without discharge until the babies are born and the mother is fit to go home.

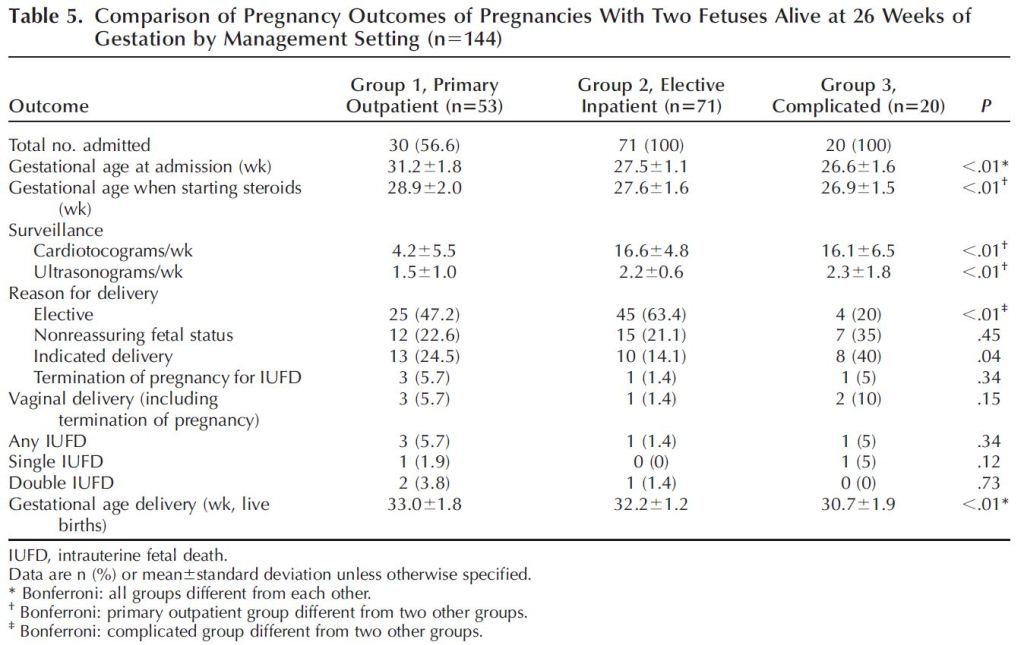

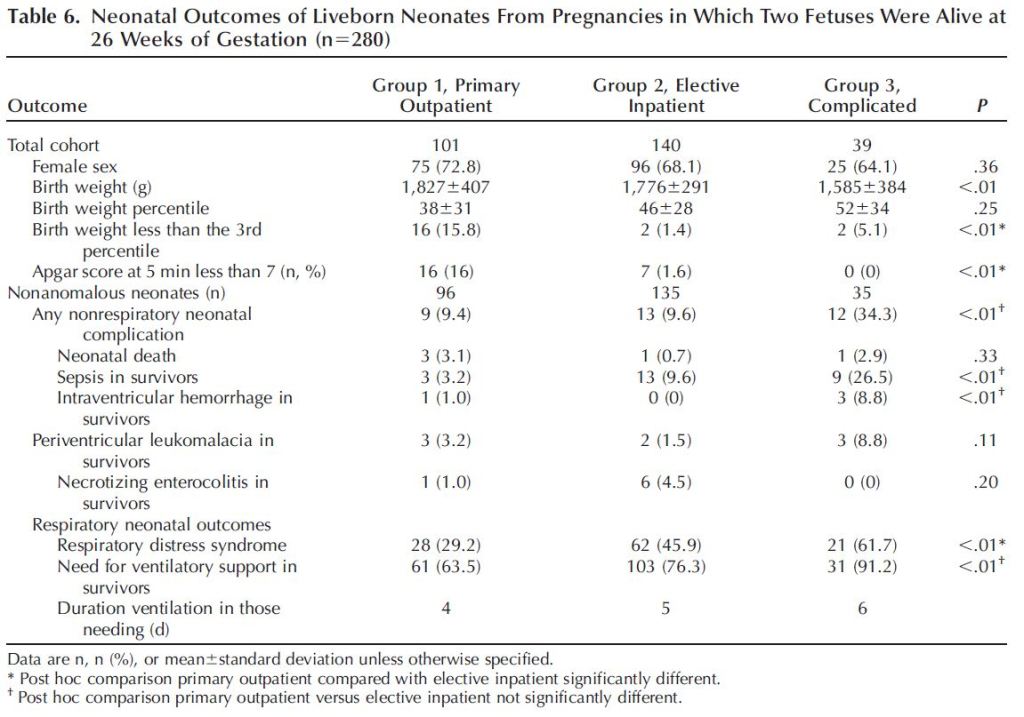

One can imagine the quality of life for the mother and her family varies significantly between the outpatient and inpatient options. Outpatient monitoring would allow one to be home with her husband and any children she may already have. Additionally, the financial burden of an extended hospital stay would be significantly reduced. Further, a mother living inpatient in the hospital may reduce her activity enough to put herself at risk of a thromboembolism, a dangerous blood clot. However, remaining inpatient would allow for more frequent monitoring and access to immediate medical attention in the event of an emergency. Further, for those families who live outside of major cities and a good distance from hospitals that can manage monoamniotic pregnancies, even twice-weekly visits may be a greater burden than just living in the hospital. Which option should you choose? You honestly may not have much of a say in how you are monitored if you wish to keep your obstetrician. One of the MFM specialists I visited favored outpatient monitoring over inpatient monitoring for some of the reasons discussed above. But my obstetrician had the final say and she was very adamant that I go inpatient. Inpatient monitoring was supported in a 2005 study that reported no intrauterine death in the cohort of patients who went inpatient, vs. perinatal loss in patients who were monitored as outpatient (Heyborne et al., 2005). The study also reported higher neonatal birthweight, older gestational age at delivery, and improved newborn survival among babies born from mothers who electively admitted themselves for inpatient monitoring (Fig. 4). One caveat to their results was that mothers who were eventually admitted for inpatient monitoring due to signs of complications (arising from, for example, TTTS) were grouped with the outpatient cohort, which could have biased results since the outpatient cohort was populated by complicated monoamniotic gestations.

A more recent study with a greater sample size (193 momo gestations vs. 96) did not find a significant difference in outcomes between patients who went inpatient and those who went outpatient (Van Mieghem et al., 2014). The study differentiated between those who were outpatient from those who went electively inpatient, as well as from those who eventually went inpatient due to complications. The authors found that outpatients delivered at a slightly later gestational age (Table 1). However, more low APGAR scores were recorded in babies born from moms who went outpatient (Table 2). In the end, the authors concluded that they did not have enough statistical power to say whether one should be monitored as inpatient or outpatient. They did advise that the monitoring be frequent. According to the authors, the patients who were monitored as outpatient in this 2014 study were likely monitored more intensely than the outpatient cohort in the 2005 study. Intense outpatient monitoring in this case meant non stress testing (NST) four times a week and ultrasounds 1-2 times a week.

Gestation beyond 34 weeks

Intense monitoring, whether inpatient or outpatient, begins around the age of viability, so between 24 and 28 weeks. But for how long should you expect to endure such tedious, albeit reassuring, surveillance? Assuming the monoamniotic pregnancy is not complicated by developmental anomalies, TTTS, or concerns from cord entanglement, the obstetric literature favors delivery between 31 and 34 weeks. Your OB will have his/her own expert opinion. In my own experience, my OB prefers delivering momos by 32 weeks, but is willing to accommodate to 34 if monitoring is increased to full-time. An influential paper (Roqué et al., 2003) recommended a 32 week delivery based on data from literature reviews that included 133 non-conjoined monoamniotic pregnancies. Data from that literature showed a significant increase in fetal mortality after 33 weeks, changing from 2-4% between 15-32 weeks to 11% from 33 -35 weeks. The percentage increased beyond 35 weeks (Figure). However, the study was criticized by later researchers, who reanalyzed the data and found that newborns delivered at 32 weeks died from fatal anomalies and so cautioned against such an early delivery (Dias et al., 2010). However, subsequent studies still support delivery before 34 weeks. The influential paper by Van Mieghem et al., 2014, discussed in the section above, recommends delivery of momo twins by 33 weeks. Figure 7 illustrates the interchange between the risk of prematurity and the threat of sharing an amniotic sac, based on their data. After 33 weeks, the risk of being in the womb outweighs any benefits.

Since 2014, different studies support different gestational ages for delivery. One retrospective study from 2015 supported delivery (including vaginal delivery!) within the 36th week, so long as there were no pregnancy complications (Anselem et al., 2015). Likewise, no babies died after delivery beyond 34 weeks (up to 36 weeks and 6 days) in a subsequent retrospective study (The MONOMONO Working Group, 2018). However, the authors of that study cautioned that their sample size of 10 twin sets delivered in the 36th week of gestation was too small to confidently recommend for future patients. Instead, the authors recommended the conventional 32 – 34 weeks and 6 days gestational age for delivery.

When considering Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALY), or the quality of life outcome from being born premature vs. risk of dying in the womb, another recent study supported an even earlier delivery time of 31 weeks (Hickock et al., 2018). The lowest rates of dying in the womb are associated with delivery at 28 weeks, while the lowest rates of newborn death and cerebral palsy occurred at 34 weeks. Thirty-one weeks was that optimal delivery time between the two outcomes (Fig. 8). However, when considering the exorbitant cost of a premature neonate to the families, the authors favored delivery at 32 weeks or even 33 weeks.

Caesarean vs. vaginal birth

Many, if not most, women prefer to deliver their babies vaginally. So a mother who is diagnosed with monoamniotic twins may be disappointed that a caesarean delivery is in her future. While some hospitals and physicians will facilitate a vaginal delivery for momos, ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) recommends that momos be delivered by caesarean section. Therefore, your hospital and physician likely will not accommodate your desire for a vaginal delivery. And you may want to resist the temptation to combat them on the subject. Afterall, vaginal birth of monoamniotic twins is risky. Caesarean delivery avoids risk of cord prolapse, where the cord of the second twin falls out of the cervix before the baby and can become clamped (Lewi, 2010).

Despite its risks, monoamniotic twins have been successfully delivered vaginally, and recent publications support vaginal delivery under optimal circumstances. For instance, vaginal delivery was deemed possible according to one study under the conditions that there were no preexisting complications, Twin 1 was head-down, and Twin 2 was not at least 30% greater in size than Twin 1 (Anselem et al., 2015). Another study published the following year compared the outcomes of 29 momo twin pairs (Khandelwal et al., 2016). Around half were delivered via c-section, and the other half were delivered vaginally. Nearly all had tangled cords at birth. All twin pairs were delivered around the same time (around 33 weeks gestational age). Survival outcomes were similar between twins born from caesarean section and the birth canal. However, the authors noted that the rate of intracranial hemorrhaging (uncontrolled bleeding in the head) was significantly lower in neonates born vaginally. Further, a nearly significant lower length of stay in the hospital and respiratory complications were correlated with that population of neonates. The authors conclude that vaginal delivery is a viable alternative delivery method for momos, although the sample size is small and is counter to the recommendation of the ACOG.

A much larger retrospective study in France compared 221 momo pregnancies (de Vergie et al., 2019). Patients were monitored both inpatient and outpatient with no significant difference in fetal mortality between the two groups. The average gestational age at time of delivery was 33-34 weeks. Of the patients who delivered at 34 weeks and beyond, one third delivered vaginally. Within the study cohort, there were not many differences in the outcomes of momo twins delivered vaginally or via c-section, except that the latter group was associated with lower Apgar scores and higher NICU submissions, once again suggesting the benefit of a vaginal delivery over caesarean section when possible.

Conclusions

If you are pregnant with monoamniotic twins in the United States, anticipate either going inpatient to the hospital, or visiting the perinatologists multiple times a week, beginning around the age of viability (26 to 28 weeks). At this time, the babies’ heartrates will be monitored with echocardiographs, and their growths will be measured from ultrasounds. Your intensive monitoring schedule will persist for the duration of the pregnancy until delivery around 32 weeks gestational age. If no risks to your babies are detectable, your physician may oblige you to let your twins gestate beyond 32 weeks in exchange for more frequent monitoring. Delivery will be via caesarian section.

Due to the rarity of this twin type, management of monoamniotic pregnancies is formed around theoretical risks. New studies suggest that some of the standard practices for managing monoamniotic gestation (e.g., inpatient monitoring, gestation up to 32 weeks, and caesarean delivery) are unnecessarily risky to the mother and babies’ quality of life. However, studies investigating monoamniotic twin pregnancy management often battle small sample sizes or are retrospective, which is problematic because one cannot test for causal relationships.

Best practices for managing monoamniotic twin pregnancy will change over time. The current protocol, which requires a demanding monitoring schedule and premature delivery by caesarean section, may not be your ideal birth plan. But it is correlated with a drastic rate increase in momo twin survival. Until more momos are born under a variety of circumstances to contribute data to future studies, be conservative and follow your physician’s advice. And breathe a sigh of relief because you and your babies are (likely) going to be okay!

References

Anselem, O., Mephon, A., Le Ray, C., Marcellin, L., Cabrol, D., and Goffinet, F. 2015. Continued pregnancy and vaginal delivery after 32 weeks of gestation for monoamniotic twins. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 194: 194-198.

de Vergie, L., Dochez, V., Lorton, F., Riteau, A., Dumas, L., Riethmuller, D., Goffinet, F., Rozenberg, P., Thubert, T., Flamant, C., Arthuis, C., and Winer, N. 2019. 358: Management of monoamniotic twin pregnancies: Retrospective multicenter study of 221 cases. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 220: S247-S248.

Dias, T., Mahsud‐Dornan, S., Bhide, A., Papageorghiou, A.T., and Thilaganathan, B. 2010. Cord entanglement and perinatal outcome in monoamniotic twin pregnancies. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology: The Official Journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 35: 201-204.

Hack, K.E., Derks, J.B., Schaap, A.H., Lopriore, E., Elias, S.G., Arabin, B., Eggink, A.J., Sollie, K.M., Mol, B.W.J., Duvekot, H.J., Willekes, C., Go, A.T., Koopman-Esseboom, C., Vandenbussche, F.P., and Visser, G.H. 2009. Perinatal outcome of monoamniotic twin pregnancies. Obstetrics & Gynecology 113: 353-360.

Heyborne, K.D., Porreco, R.P., Garite, T.J., Phair, K., and Abril, D. 2005. Improved perinatal survival of monoamniotic twins with intensive inpatient monitoring. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 192: 96-101.

Hickok, R.A., Walker, A.R., and Caughey, A.B. 2018. 236: When to deliver monochorionic-monoamniotic twins undergoing inpatient continuous fetal monitoring–A decision analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 218: S153-S154.

Khandelwal, M., Revanasiddappa, V.B., Moreno, S.C., Simpkins, G., Weiner, S., and Westover, T. 2016. Monoamniotic Monochorionic Twins—Can They Be Delivered Safely Via Vaginal Route? Obstetrics & Gynecology 127: 3S.

Lewi, L. 2010. Cord entanglement in monoamniotic twins: does it really matter? Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology: the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 35: 139-41.

MONOMONO Working Group. 2018. Inpatient vs outpatient management and timing of delivery of uncomplicated monochorionic monoamniotic twin pregnancy: the MONOMONO study. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology 53: 175-183.

Myrianthopoulos, N.C. 1975. Congenital malformations in twins: epidemiologic survey. Birth Defects Original Article Series 11: 1-39.

Roqué, H., Gillen-Goldstein, J., Funai, E., Young, B.K., and Lockwood, C.J. 2003. Perinatal outcomes in monoamniotic gestations. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 13: 414-421.

Rossi, A.C., and Prefumo, F. 2013. Impact of cord entanglement on perinatal outcome of monoamniotic twins: a systematic review of the literature. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 41: 131-135.

Tongsong, T., and Chanprapaph, P. 1999. Evolution of umbilical cord entanglement in monoamniotic twins. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology: The Official Journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 14: 75-77.

Umur, A., van Gemert, M.J., and Nikkels, P.G. 2003. Monoamniotic-versus diamniotic-monochorionic twin placentas: anastomoses and twin-twin transfusion syndrome. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 189: 1325-1329.

Van Mieghem, T., De Heus, R., Lewi, L., Klaritsch, P., Kollmann, M., Baud, D., Vial, Y., Shah, P.S., Ranzini, A.C., Mason, L., Raio, L., Lachat, R., Barrett, J., Khorsand, V., Windrim, R., and Ryan, G. 2014. Prenatal management of monoamniotic twin pregnancies. Obstetrics & Gynecology 124: 498-506.

Feel free to share your monoamniotic pregnancy game plan in the comments below!